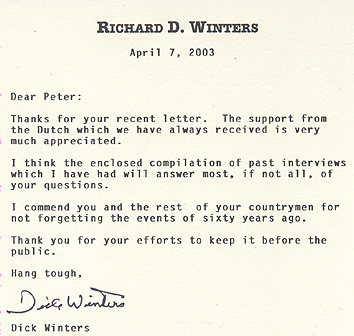

In March 2003, I wrote a letter to Dick Winters and I enclosed the compilation photo I made of the 46 Easy Company Veterans who were present in Normandy on June 6, 2001. I asked him some questions and a few weeks later I received a big envelop from Dick Winters with a Franklin & Marshall Magazine.

Together with that magazine I received the greatest Award I could ever imagine:

a compliment from Dick Winters.

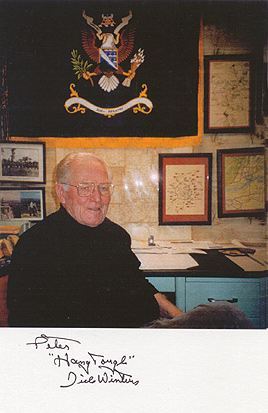

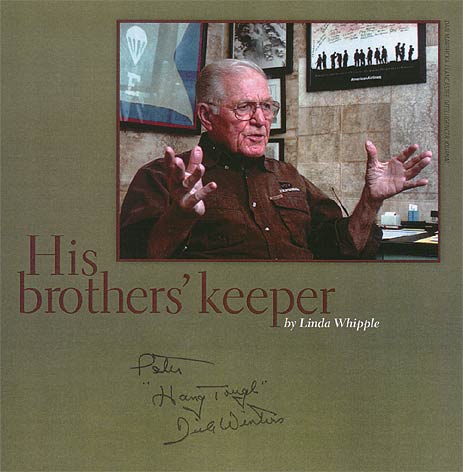

Winters is surrounded by maps, photos, and memorabilia that serve as continual reminders of his service to the country as commander of E “Easy” Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division.

A shadow box filled with battle decorations hangs on the wall behind his office door, along with a map of Utah Beach (Normandy) that goes back to Roman times, and Winters’ signature “Hang tough, pardner” cowboy poster. On the opposite wall is the company flag, and to the left of it, framed and autographed photos of military top brass, including Secretary of State Colin Powell, as well as photos of Winters as a soldier and of Damian Lewis, the actor who portrayed him in the Emmy Award–winning Band of Brothers HBO miniseries based on the book by Stephen E. Ambrose. “He started off on the weak side,” the usually laconic Winters says of his miniseries counterpart. “I wasn’t so hot when I started out either.”

Above Winters’ desk is the road map of Bastogne that he carried with him the entire time that Easy Company held a 17-mile perimeter around the Belgian city during the Battle of the Bulge, and a framed Band of Brothers poster signed by the surviving men of Easy Company—his “family.”

Millions of TV viewers worldwide watched the company’s saga unfold—from training at Camp Toccoa, Ga., through D-Day and the Battle of the Bulge, to the capture of

Adolf Hitler’s “Eagle’s Nest” Bavarian chateau. Even more now have access to the story on video and DVD. Winters is flooded by fan mail from people of all ages who recognize him as a genuine hero. He is proud of what he has accomplished, but he never intended to become a celebrity. Telling the story of Easy Company was his motivation from the start.

The men of Easy Company were highly motivated citizen soldiers. They had volunteered for the paratroopers, a new and experimental regiment, and by the late spring of 1944, they had become an elite company of airborne light infantry. “At the peak of its effectiveness, in Holland in October 1944 and in the Ardennes in January 1945, it was as good a rifle company as there was in the world,” Ambrose wrote.

Easy Company distinguished itself early. In its first combat action, during the early morning hours of D-Day, a company platoon led by 1st Lt. Winters took out a German battery unit looking down on Utah Beach. Winters swivels his desk chair around to face a map of Normandy, where the 101st Airborne, known as the Screaming Eagles, jumped behind enemy lines on D-Day as part of the massive Allied invasion of German-occupied France.

“We

landed here,” he says, pointing to an area outside the little French

village of Ste. Mère-Eglise. “The German defense was to flood

the low lands. The water was two feet to over six feet deep—that was

part of their defense. They didn’t need a lot of men to stop any troops

that were landing.”

With

only 12 men, Winters launched a daring frontal assault on the Germans, hitting

them from different directions at once. He and his men succeeded in opening

up one of four causeways leading to Utah Beach, which made it easier for the

invading Allied forces to come inland. Winters received

the disinguished service cross for his valor.

Picking

up a long metal pointer, Winters turns and points to a map of Holland. “We

jumped north of Eindhoven,” he says, “Then the job was to hold

the road open.” But it couldn’t be done and Operation Market-Garden,

as the high-risk offensive was called, ultimately failed. Easy Company was

forced to retreat to the “island,” a flat agricultural area below

sea level, where dikes held back the floodwaters of the Lower Rhine.

Capt.

Winters, by then, organized a patrol, consisting of a squad and a half from

the 1st platoon, and led an attack on a full company of SS troops that had

come across the river by ferry from the north and was attempting to infiltrate

the island. What he didn’t know was that another SS company had crossed

over, too.

He

took the Germans by surprise. “By dumb luck, I caught them [the Germans]

in their winter overcoats. They were all packed together.” The Germans

were lying with their heads down to avoid the covering machine-gun fire. “I

was shooting at their backs. I had two companies on the run.”

In

their long overcoats, the Germans moved slowly and awkwardly as they attempted

to run away. Easy Company kept up the fire, while Winters called for artillery

support. His men had to scatter when the German artillery started up and the

shelling became too intense. With just one platoon, however, Winters had routed

two German companies of about 300 men. A couple of days after the attack,

Winters was promoted to executive officer of the 2nd battalion. He rose to

major just before the Army moved into Germany. Ambrose once told him, after

writing Band of Brothers, “From now on, Winters, and for the rest of

your life, your subject is leadership. You’ve got it.”

So how does

he define leadership? “It’s something you have within you that

gets the job done,” explains Winters, a corporate manager in the feed

business before he retired. “You start with a cornerstone—honesty—and

from there you build character, you build knowledge. With honesty goes being

fair, making decisions, and being right, most of the time.”

Old soldiers

say the bond created in wartime is special, forged by a heightened sense of

caring and responsibility for one another. “You remember that my life

depends on you and your life depends on me,” Winters explains, adding

that men who have this kind of bond cherish it and don’t want to lose

it.

Maybe

it isn’t such a coincidence that many of the men in Easy Company had

the nurturing of good mothers. “I had a wonderful mother—very

conservative,” Winters notes. “My mother came from a Mennonite

family. Honesty and discipline were driven into my head from day one.”

His

family lived on South West End Avenue in Lancaster, close to campus. He studied

business at Franklin & Marshall and worked hard digging pole holes for

Edison Electric, shoveling snow, and cutting grass to afford his studies.

When

he enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1941, his Aunt Lottie bought him a diary.

Soon after the D-Day battle, Winters was hit in the leg during a skirmish

and was laid up for a few days. That’s when he began to write.

Using

the training he received in college, Winters became a student of war. “I

must remember this. I must remember this,” he kept telling himself.

He wrote down all the dates and just a few words, but in the sequence in which

they happened—with no rewrites or edits later to alter the truth. “When

you write the ledger in combat and you’re surrounded by people you fight

with, you don’t exaggerate. You make darn sure you’re conservative.”

He sent the diaries home to his parents for safekeeping.

Finding

the right person to tell the story of Easy Company wasn’t easy. Before

he found Ambrose, Winters was in touch with another writer who first wanted

to know: “How much money do you have?” Ambrose simply said: “Send

me your memories.” He had some time between projects and thought he

could work in the story. So Winters, with the help of his wife, Ethel, who

typed up his voluminous notes, did just that. In some passages, Winters points

out, Ambrose used his diaries almost word for word.

Ambrose

returned the diaries to Winters—along with the other stories he collected

from the surviving members of Easy Company—after completing his work

on Band of Brothers.

“I spent one whole winter going through that,” Winters recalls.

“I made a file for each and every man, so it’s all together and

it’s all there.” At the right time, he said, his files will go

to the Army War College in Carlisle, Pa., for future historians to use.

Actor

Tom Hanks, who coproduced the HBO miniseries with Steven Spiel-berg, met Winters

and became interested in the story of Easy Company while researching his starring

role in Saving Private Ryan.

When

Ambrose sold the rights to Hanks, Winters sent the actor a complete copy of

his diaries. “You send me golden nuggets,” Hanks replied. In return,

Hanks found out that Winters doesn’t drink or smoke, but has a taste

for ice cream. So now Hanks sends Winters four half-gallon containers of ice

cream from a famous Oklahoma City manufacturer every year for his birthday.

With

the deal struck, teleplay cowriter Erik Jendresen came to Hershey to hammer

out “the bible”—a 250-page outline for the miniseries. That

outline was divided up among six writers who took different episodes of the

film and interviewed the surviving members of Easy Company in depth.

“The

writers are always creative,” says Winters, who would ask them: “Why

couldn’t you use it the way I remembered it?” But he acknowledges

that they need to look at the material from the audience’s point of

view. On the real D-Day, for example, the guns were camouflaged. “But

you can’t make a picture with guns camouflaged.”

After watching the Emmy Award presentations on TV all his life, Winters never imagined that last September, he would be living it: that a limo would whisk Ethel and him away to the airport for a direct flight to Los Angeles; or that he would be put up at one of the finest hotels in Beverly Hills, and a masseuse would arrive at his door with a table and oils to give him a nice massage before the big night.

And then,

of course, there was the awards ceremony itself, followed by the

acceptance speech he gave on behalf of all the men of Easy Company,

and the celebration afterward.

The entire experience was like a dream. But the awards ceremony that Winters

is proudest of attending took place more than a year earlier in Hyde Park,

N.Y., where he was one of five World War II veterans to receive the 2001 Franklin

D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms/Freedom from Fear Award.

NBC news anchor Tom Brokaw presented the Freedom from Fear awards that day.

The courage and service demonstrated by these veterans, Brokaw said, “made

possible a world of peace and justice and dreams that we continue to fulfill

today.”

Heady stuff. But to regain his sense of perspective, Winters has only to reread his own diaries.

“My story today is the same as it was in 1944,” he says. “I intend to keep it that way.”

'My home is your home'

Among the “very sincere” letters Winters has received since the broadcast of Band of Brothers is one that closes with a brief, open-ended invitation: “If you ever come to Argentina,” the letter writer states, “my home is your home.”

“I

thought, oh my god, that’s beautiful,” Winters says. “He

put it together exactly right.”

That someone would offer his home, to Winters, is the ultimate expression of kindness—and he knows from personal experience what that means.

In September 1943, the 101st Airborne landed in England after spending seven days packed together so tightly aboard a transport ship that “you can’t move without bumping into somebody.” The men were taken to the little village of Aldbourne, where the troops were bedded down for the night, and the officers retreated to a building set aside for them. But it was just as crowded in there.

“I got up the next morning and just wanted to get away from everybody,” recalls the chiseled Winters, his voice soft and his eyes darting back and forth as he visualizes the scene. “On a Sunday morning, what do you do? You go to church.”

Afterward, Winters still wanted to be alone so he went to the cemetery adjacent to the church, walked to the top of a hill and sat down by himself. He could see an elderly couple fussing around a new grave. They finished tidying up and then came over to sit on the bench beside him and visit.

“Would you like to come to tea at 4 o’clock?” they asked.

Homesick and wondering whether he’d ever see home again, Winters was overjoyed by the invitation. He went to tea. A couple of days later, battalion leaders decided they needed more billets for officers. The elderly couple agreed to take two men provided Winters was one. Their home became his home for eight months.

Mr. Barnes was a lay preacher in the church and Mrs. Barnes played the organ. “I realized that to go to church was a privilege, so I went to church,” Winters says.

On

a typical evening, he would be reading when he would hear a knock on his door,

and Mrs. Barnes would ask: “Lt. Winters, would you like to come down

and listen to the news?”

After listening to a BBC broadcast on the radio, they gathered around the

table. Mr. Barnes read a portion from the Bible, and Mrs. Barnes served bread—no

sweets, no jelly, just bread. Then Mr. Barnes would announce it was time for

bed.

“I loved it. I appreciated it,” Winters says emphatically. “I had found a home and these people had adopted me.”

While

the other soldiers were out carousing in the pubs, Winters was studying and

reading at home every night—and gaining the respect of his men.

“The men know what you’re doing—they know this,” he

says. “They kid about it, but they respect it.”

Winters returned to Aldbourne after the D-Day invasion of Normandy, having won the Distinguished Service Cross and a spot on the BBC news. Mrs. Barnes greeted him like his own wonderful mother would have done. “I’m so proud of you,” she told him. “I just knew you would do good.”

Editor’s Note: Franklin & Marshall magazine is collecting stories of World War II alumni for a website archive. Send stories (500 words or less) to magazine@fandm.edu, or to Editor, Franklin & Marshall magazine, P.O. Box 3003, Lancaster, PA 17604.

PAGES:

I do not intend to infringe on any copyrights.I just want to promote Band of Brothers© and pay a tribute to everyone who was involved in giving back our freedom in wwII

Any comments about the text or photos on this page please mail me